UPDATE dated 16th February 2017 - Fromelles: Australia picks a fresh fight with Britain over a 100-year-old battle

Fromelles: Australia picks a fresh fight with Britain over a 100-year-old battle

The spat between Australia and Britain over the “banning” of the families of the British soldiers who fell at the Battle of Fromelles in France in July 1916 from this years commemoration is historically confused and based on an anachronistic understanding of Australian and British connections during the war. It’s also an example of the danger of linking your national identity too closely to your military history.

What makes it so absurd is that many of the 5,513 casualties from the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) at Fromelles were British-born migrants to Australia. But modern Australian officialdom is (presumably inadvertently) endorsing the view that the battle was an exclusively “Australian” tragedy for which the blame is fixed squarely on the arrogant “imperialist” British generals who treated colonial forces as cannon fodder.

Although the subject of half a dozen books, including chapters of Australia’s detailed official history of the war, Fromelles has become the subject of misunderstanding and myth in Australia. It is supposed to have been “forgotten” (though it was long remembered as Fleurbaix – the name of the village from which Australian and British troops attacked – rather than Fromelles, which the Germans defended). It has become seen popularly as “the worst night in Australian military history” – a notorious instance in which callous and incompetent British generals sent Australians to their deaths for no purpose.

Fromelles was mounted as a feint to draw German troops away from the Somme and was the first major engagement on the Western Front involving the recently arrived Australian forces. While modern research has questioned the established view of the battle as a complete military failure, historian Gary Sheffield has argued that it nonetheless “further damaged Australian faith in British generalship, already shaken after Gallipoli”.

Indeed, one modern Australian authority claimed: “More than any other battle, Fromelles cleaved a sense of separateness of the Australian soldier from Great Britain”. Having rallied to the “Mother Country” in 1914 and “marched to war as the sons of Great Britain”, experiences such as Fromelles meant that by war’s end, “our blokes … returned as Australians”.

The reason for the high profile of Fromelles in Australia’s commemoration is that a mass grave, which had been overlooked in the post-war clean-up, was discovered in 2008 at Pheasant Wood near Fromelles where the Germans had buried 250 Australian and British dead in 1916. The discovery resulted in their remains being interred in the first new Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemetery opened on the Western Front in decades. Pheasant Wood cemetery soon became a place of pilgrimage for Australians visiting northern France in search of Australia’s Great War.

Awareness of the historical context of the battle has clearly informed some British coverage of the decision by the Australian Department for Veterans Affairs to invite only the families of Australians to the memorial ceremony this year. Coverage in the UK has suggested that “banning” the relatives of the 1,547 British casualties of Fromelles, exclusively focuses on the Australian soldiers lost in light of the smaller, but still significant, British casualties.

In response, an Australian spokesman noted in The Times (paywall) that Britain’s own Somme commemoration of July 1 2016 will only be open to British citizens. It’s clear the war’s centenary is being shaped by modern national and state agendas.

Blighty born and bred

But there is an anachronism at the very heart of this spat because – as the military historian Andrew Robertshaw said: “A surprisingly high proportion of the Australian Imperial Force were not actually born in Australia.”

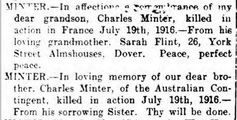

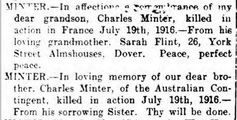

Among the names included under the headline “Australian casualties” in The (Melbourne) Argus of August 22 1916 was that of Private Charles Herbert Minter. He was just one of 5,513 soldiers of the AIF who had been killed, wounded, or captured during the bloody attack on Fromelles of July 1916.

Minter was born in Dover, in the English county of Kent, in 1888. He arrived in Australia in October 1910 at the age of 22 and enlisted less than five years later in the Australian Imperial Force in July 1915. In doing so, he was typical of many of the so-called “new chums” (as recent arrivals from Britain were colloquially called). One estimate suggests that 27% of the first AIF contingent were British born, with estimates for the war as a whole varying between 18% and 23%.

Minter was born in Dover, in the English county of Kent, in 1888. He arrived in Australia in October 1910 at the age of 22 and enlisted less than five years later in the Australian Imperial Force in July 1915. In doing so, he was typical of many of the so-called “new chums” (as recent arrivals from Britain were colloquially called). One estimate suggests that 27% of the first AIF contingent were British born, with estimates for the war as a whole varying between 18% and 23%.

Australia was hardly unusual among the Dominions in this respect – 26% of the first contingent of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force were British born, while 64% of the first contingent of the Canadian Expeditionary Force had been born in Britain. As one of these men commented years afterwards: “I felt I had to go back to England. I was an Englishman, and I thought they might need me.”

That Minter’s British descendants (his “sorrowing sister” posted a death notice in tribute to her “dear brother” in the Dover Express in August 1916) would not technically be eligible to attend the Fromelles commemoration highlights the way that the multi-layered identities of these British-born “diggers” (and “Kiwis”, and “Canucks”) have been rendered one-dimensional in the century since the guns fell silent.

Imperial transformation

To understand Australia’s transformation from imperial loyalty in 1916 to disdainful exclusion in 2016 requires a quick survey of the relationship between war and nationalism in Australia.

The Great War, which began just 14 years after Australia’s federation, brought a flowering of national identity and pride. Australians proudly extolled the Anzacs’ endurance in the ill-fated Gallipoli campaign. At first overawed by British military prowess, repeated disasters and debacles challenged the simple loyalty of 1914. At Versailles, the Australian prime minister, Billy Hughes, represented his country’s interests as different to Britain’s.

World War II reinforced these resentments. Winston Churchill (regarded as the author of Gallipoli) committed Australian troops to the disastrous Greek campaigns in 1941. He was held responsible for the fall of Singapore, in which the Japanese captured an Australian division. A month later Churchill tried to send Australian troops to Burma, where they would have been lost had not the Australian prime minister, John Curtin, insisted on their return home. Australia turned instead to America and its foreign policy has been focused on the US rather than the UK ever since.

Prince Charles attending the 2010 Fromelles commemoration service. Reuters/Farid Alouache

Each of these instances involve facts and arguments disregarded in the popular story of Australia’s wars. For example, that British troops suffered greater casualties in all these campaigns is ignored. For 40 years, many Australians have adopted an assertively nationalist view of Australia’s part in the world wars. Britain has been transformed from benevolent senior partner to malicious, incompetent or uncaring exploiter of Australian lives. At Fromelles, the new nationalist myth runs, bastard Brit generals sacrificed our diggers for no good reason.

No matter that those “Australians” (including those born in Britain) had joined to serve the empire, or that they died beside British troops; or that Australian generals were often complicit in their deaths. Australia’s nationalist myth is so powerful that it has now reportedly resulted in Australian officials disdaining the families of the British dead of Fromelles. They have done what the Kaiser’s propaganda could not.

Abstract taken from

Top of Page

Minter was born in Dover, in the English county of Kent, in 1888. He arrived in Australia in October 1910 at the age of 22 and enlisted less than five years later in the Australian Imperial Force in July 1915. In doing so, he was

Minter was born in Dover, in the English county of Kent, in 1888. He arrived in Australia in October 1910 at the age of 22 and enlisted less than five years later in the Australian Imperial Force in July 1915. In doing so, he was

On 8th October 2016 the Antrim and Down branch of the WFA held its annual conference on the history, legacy and importance of political and military events during 1916. Twenty-nine people attended.

On 8th October 2016 the Antrim and Down branch of the WFA held its annual conference on the history, legacy and importance of political and military events during 1916. Twenty-nine people attended.