Barton's Boys

Letters of thanks written by ten young men from St Mark’s Parish, Dundela in East Belfast, serving at the Western Front, in response to parcels sent out to them from their home parish at Christmas 1917 provide a poignant seasonal theme for the final Archive of the Month of the year, digitized at the RCB Library, Dublin. While many collections of letters written from the Front are found in other repositories and in private custody, the survival of a collection in a parish context is rare, and to this end the RCB Library is making them available to a worldwide audience, in the hope that descendants of the men might come forward to tell their stories after the Great War. Records show that all ten bearing the surnames Brewis, Cleary, Commerford, Hanna, McKay, McKernon, Millikin, Palmer (two brothers) and Sterrett were fortunate enough to survive the conflict, but as to what happened them when they returned home is less certain.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Established in 1876, Dundela was the first ‘modern’ parish to be created in the growing suburbs of east Belfast and provides evidence of Belfast’s rapid expansion from the latter half of the 19th century onwards. Situated in a prominent position on the crest of Bunker’s Hill, on the main Holywood Road going towards the Bangor Road, the parish church’s distinctive sandstone bell–tower was once visible from all over Belfast. Whilst now subsumed into greater Belfast today, it continues a conspicuous landmark. At the turn of the 20th century, the social profile of Dundela parish was varied and interesting – representative of Belfast’s diverse and growing population. Some of Belfast’s most prominent families had their houses and villas within its boundaries, and the social makeup was further enriched by the families of numerous working men earning the weekly wage in Belfast’s factories, mills and shipyards, and their families, many of whom resided in the village of Strandtown.

Irrespective of social class, the outbreak of hostilities in Europe in August 1914 united parish men and their families in the cause to defeat a common enemy. Dozens of young male parishioners went off to fight. In October 1914, the parish magazine recorded an initiative aimed at involving the women parishioners in the war effort. Entitled ‘Knitting for Soldiers’, it represented the parish’s contribution to a larger scheme of ‘doing something for the comfort of our men at the front’, and continued throughout the War. In March 1918, it was further reported that: ‘several letters have been received from parishioners in France, thanking the congregation for the New Year presents and saying how useful they were in the winter weather’.

All ten letters were written between the end of January and late February 1918, but relate to parcels sent the previous Christmas. They were addressed to Dundela’s new rector, the Reverend Arthur Barton, appointed to Dundela just four months before the outbreak of hostilities and who continued in that position until 1925. Barton was serving his first incumbency as rector of a parish, and following an 11–year stint in Dundela, went on to have a distinguished clerical career as rector of Bangor (1925–30), also serving as treasurer, precentor and eventually archdeacon of Down (1927–30), before his first episcopal appointment as Bishop of Kilmore (1930–39), and finally as Archbishop of Dublin (1939–56).

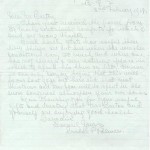

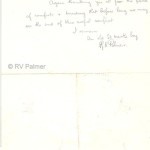

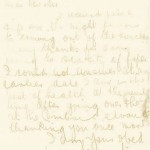

A file of his personal papers that survives from his time as rector reveals the activities that focused his particular attention during the War: the adult and junior choirs; the Church Lads’ Brigade; the Sunday School and annual excursion for children and their families, and the parcel scheme of comforts for those at the Front. Each letter of thanks reveals that the men deeply appreciated receipt of their comfort parcels and the thoughts of people at home, and some also described what they were going through. Their words clearly meant a great deal to Barton because he felt them important enough to keep together in an envelope marked simply ‘Soldiers’ Presents’.

It is remarkable that these letters have survived. Their provenance is somewhat unusual because they actually turned up in the basement of Kilmore See House, just outside Cavan town, in the context of a much larger volume of other diocesan papers. It was in this house that Barton, like other bishops of Kilmore, had resided between 1930 and 1939. He obviously took the papers with him from Bangor, but for whatever reason, they did not accompany him to Dublin after his stay in Cavan and remained buried in a cupboard in Kilmore See House until the archival contents of the house were transferred in their entirety to the RCB Library in Dublin in 2007.

Taken together, the letters provide poignant descriptions of the realities of that conflict and its impact on the personal lives of the Brewis, Cleary, Commerford, Hanna, McKay, McKernon, Millikin, Palmer and Sterrett families in this particular Belfast parish. Having digitized them, the RCB Library hopes that the descendants of the ten writers might get in touch to complete their stories.

To view the ten letters with additional details about each letter writer extracted from the parish registers of baptism, marriage and burial, and the 1911 Census of Ireland, visit: www.ireland.anglican.org/library/archive

For further information please contact:

Dr Susan Hood

RCB Library

Braemor Park

Churchtown

Dublin 14

Tel: 01–4923979

Fax: 01–4924770

E–mail: susan.hood@rcbdub.org